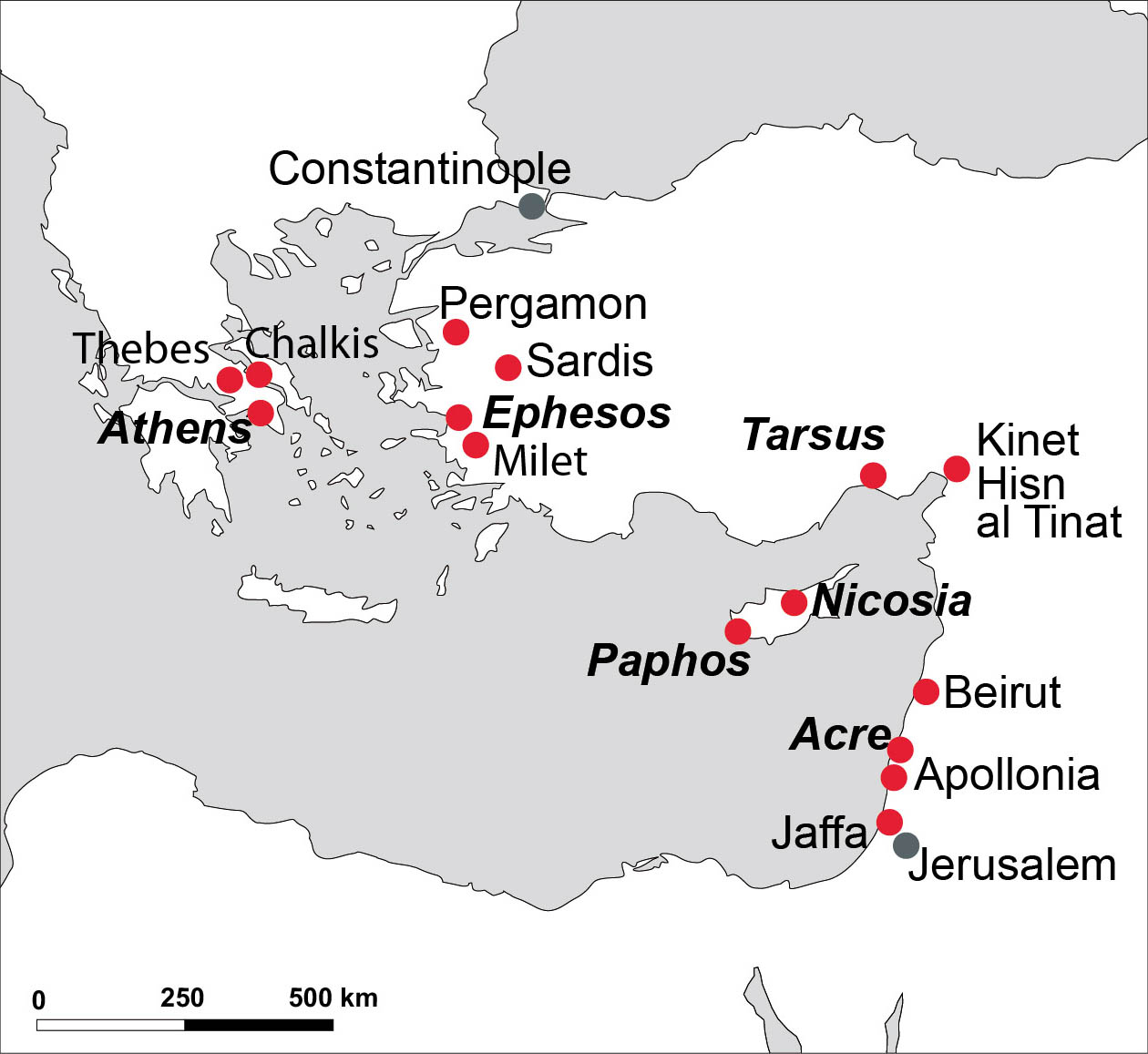

map © MOM, S.Y. Waksman

ACRE

Acre was one of the main harbors of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem during the Crusad er period. Following its conquest in 1104 by Baldwin I with the aid of the Genoese fleet, Acre emerged as a leading eastern Frankish port in the twelfth century. After Jerusalem was captured by Salāh ad-Dīn in 1187, Acre became the capital city of the second Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and was for the next one hundred years the seat of the Crusader government, as well as of the Patriarch of Jerusalem (for most of this period) and of the heads of the military orders. These functions, in addition to the thriving commerce of its busy port, made Acre the most important and cosmopolitan city in the Frankish East, playing a pivotal role in the maritime trade with Europe, the Muslim states and the Byzantine Empire, as well as continuing to serve as a gateway for pilgrims to the Holy Land until the fall of the Latin Kingdom in 1291 CE. The presence of representatives of the three leading maritime cities (Genoa, Pisa and Venice), who resided in quarters within the town, contributed greatly to the city’s growing commercial importance.

er period. Following its conquest in 1104 by Baldwin I with the aid of the Genoese fleet, Acre emerged as a leading eastern Frankish port in the twelfth century. After Jerusalem was captured by Salāh ad-Dīn in 1187, Acre became the capital city of the second Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and was for the next one hundred years the seat of the Crusader government, as well as of the Patriarch of Jerusalem (for most of this period) and of the heads of the military orders. These functions, in addition to the thriving commerce of its busy port, made Acre the most important and cosmopolitan city in the Frankish East, playing a pivotal role in the maritime trade with Europe, the Muslim states and the Byzantine Empire, as well as continuing to serve as a gateway for pilgrims to the Holy Land until the fall of the Latin Kingdom in 1291 CE. The presence of representatives of the three leading maritime cities (Genoa, Pisa and Venice), who resided in quarters within the town, contributed greatly to the city’s growing commercial importance.

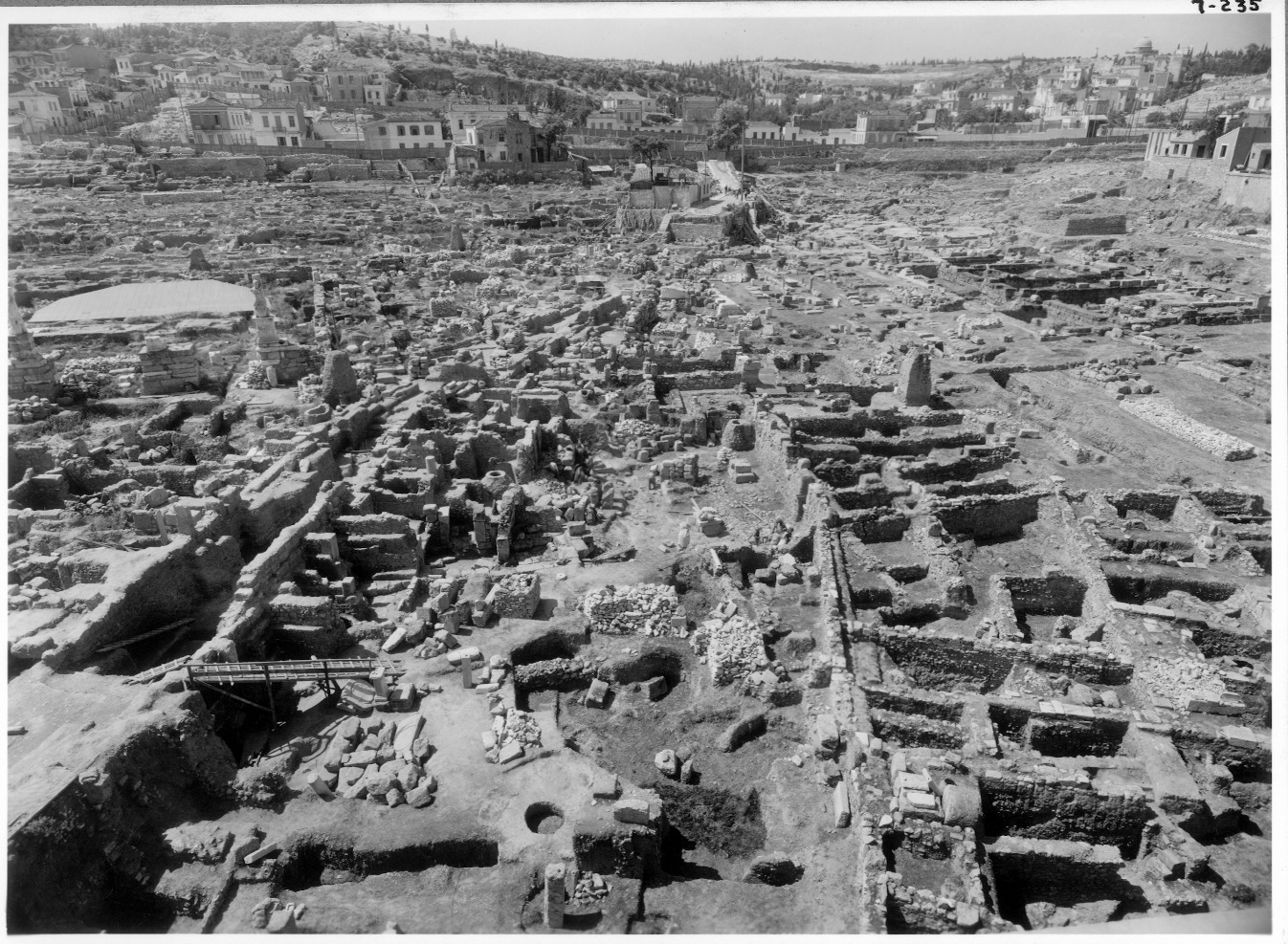

Archaeological excavations have been conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority since 1990, partly commissioned for the promotion of tourism, and partly as salvage excavations due to the growth and development of the modern town and the Old City. These archaeological excavations have revealed different parts of Crusader-period Acre. Two large scale excavations were conducted, at the Hospitaller compound, the headquarters of the knights of St. John, and at the 'Knights Hotel' (cf. photo, left), a residential and commercial quarter. Together with the numerous other smaller excavations, they underscore the centrality of Crusader Acre by illuminating its densely populated nature and the variety of its public and domestic buildings, shops, streets and material culture remains. The Old City of Acre received the status of a UNESCO World Heritage site (2001), further enhancing the importance of the archeological finds.

Among other finds, many types of local and imported ceramics were unearthed in the excavations, and reflect the types in use by a cross-section of the population of Acre during the period of Frankish rule (12th – 13th centuries). The local pottery includes two main groups. The first consists of simple, unglazed pottery produced in Acre, and especially includes "Acre bowls" found in large quantities in the Hospitaller compound. The latter could have been used as disposable containers to feed the poor, the sick, and the pilgrims. The other major group includes glazed cooking and table wares manufactured in Beirut. As Beirut was part of the same Crusader Kingdom as Acre at the time, they are considered local as well, as opposed to ceramics imported to Acre from a wide range of regions throughout the Mediterranean (cf. photo, right). These mainly correspond to glazed bowls and account for some 30% of the entire pottery assemblage. Pottery was imported from South-Eastern Turkey (Port St. Symeon Ware), Asia Minor, Cyprus (Paphos-Lemba ware), Greece (Fine Sgraffito and Aegean Ware), northern Italy, southern Italy and Sicily (Proto-maiolica), southern France, Catalonia in Spain, and North Africa (Blue and Manganese ware), as well as from beyond the Mediterranean, including China (Celadon).

adapted from E.J. Stern

photos © H. Smithline, Israel Antiquities Authority

© I. Greenberg (aerial view of Acre)

More information and bibliography...

PAPHOS and NICOSIA

During the 13th century, Paphos was the main port connecting Cyprus with the Levant. Nicosia, an inland site farther from the ports, was the Capital of the island. Three excavation sites were initially considered for the POMEDOR project: the convent of Agios Theodoros in Nicosia, and the Fabrika and Odos Ikarou sites in Paphos.

Agios Theodoros Convent, Nicosia

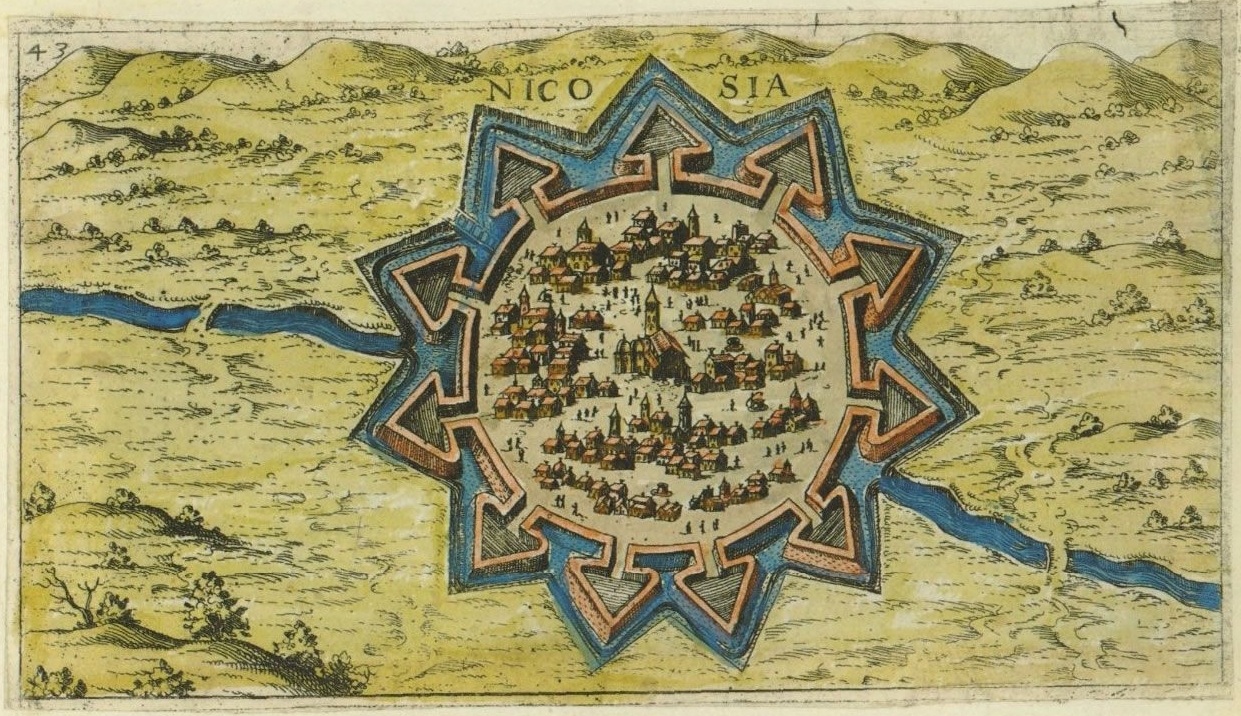

The convent of Agios Theodoros is outstanding in being an urban female monastery of the Cistercian order in the Latin East. The site is well-documented in historical sources. The monastery was founded around 1237 a by the Ibelin family, one of the most important families in the Frankish East and Cyprus, and razed to the ground in 1567, as part of the fortification works in preparation to the Ottoman invasion.

Excavations were carried out by the Department of Antiquities of Cyprus under the supervision of Eftychia Zachariou, and a multi-disciplinary study is underway. The team includes a historian, an architect, and a number of specialists for the archaeological assemblage, among them an archaeozoologist, a physical anthropologist and a glass specialist. The pottery is studied by Smadar Gabrieli.

In spite of the special character of the site we believe that the assemblage of Agios Theodoros may give us an insight not only to life in a monastery, but also to Frankish households of the period.

Odos Ikarou, Paphos

The site of Odos Ikarou in Paphos is a built Roman tomb that was excavated by Dr Evstatios Raptou from the Department of Antiquities of Cyprus. Like other built tombs of the period, the structure was occupied in the 13th century, and was eventually abandoned, the inhabitants leaving behind a complete household, comprising over 150 vessels. The significance of the assemblage from Odos Ikarou lies in it being an undisturbed, and, we believe, a complete household pottery assemblage. The custom of using built Roman and Hellenistic tombs in the Medieval period, whether for living, as storage spaces or for other activities, is well known, as for example in the cemetery known as the Tombs of the Kings, which lies not far from modern-day Paphos.

Fabrika Hill, Paphos

The site of the Hellenistic–Roman Theatre of Paphos at Fabrika Hill (cf. photo), was excavated by the University of Sydney under the direction of Prof. Richard Green, and later under Drs. Craig Barker and Smadar Gabrieli. The Medieval occupation over the ruins of the theatre began in the 13th century, when the area was the site to one of the famous Paphos-Lemba workshops that produced Cypriot table wares for local consumption and for export to the Crusader Levant. The site, and the workshop, came to a violent end by an earthquake at the beginning of the 14th century, and following an unknown period of abandonment, was reoccupied. There is evidence of at least low-level occupation in the 15th century, and the remains intensify during the 16th century and later.

Samples for analysis for the POMEDOR project were chosen from the misfires and kiln furniture of the 13th century workshop, and from the assemblage that dated the destruction of the site at the beginning of the 14th century. This assemblage was interpreted as a result of clearing the site after an earthquake since it was a single-episode deposit that was sealed in a well, and included in addition to household and workshop debris, a number of complete non-edible animal skeletons, with a high proportion of young ones.

R.S. Gabrieli

map of Nicosia (1597) from Giacomo Franco, Viaggio da Venetia a Constantinopoli per Mare

photo © R.S. Gabrieli

Bibliographical indications

Cook, H.K.A., Green, J.R., 2002, Medieval Glazed wares from the theatre site at Nea Pafos, Cyprus: Preliminary Report, RDAC, 413-424.

Gabrieli, R.S, 2006, Silent Witnesses: The Evidence of Domestic Wares of the 13th-19th Centuries in Paphos, Cyprus for Local Economy and Social Organisation, PhD thesis, University of Sydney.

Gabrieli, R.S., 2008, Towards a Chronology - The Medieval coarse ware from the Tomb on Icarus Street, Kato Pafos, RDAC, 423-454.

Green, J.R., Gabrieli, R.S., Cook, H.K.A., Stern, E.J., McCall, B., Lazer, E., in press, Paphos 8 August 1303 Snapshot of a Destruction.

Papanikola-Bakirtzis, D., 1993, Cypriot medieval glazed pottery: answers and questions, in The Sweet Land of Cyprus, Nicosia, 115-130.

Papanikola-Bakirtzis, D., 2004, Colours of medieval Cyprus, through the medieval ceramic collection of the Leventis Municipal Museum of Nicosia, Nicosia.

Raptou, E., 2006, The built tomb in Icarus Street, Kato Pafos, RDAC, 317-342.

ATHENS

Athens during the Byzantine, Frankish and Ottoman periods has only recently gained full attention in the archaeological record. The systematic excavations of the American School of Classical Studies at the Athenian Agora and numerous rescue excavations by the Greek Archaeological Service have brought to light an abundant number of fragments of the history of the city. This archaeological evidence is still awaiting close study and historical interpretation, which will supplement the meager amount of information provided by medieval and early modern literary sources.

Athens during the Byzantine, Frankish and Ottoman periods has only recently gained full attention in the archaeological record. The systematic excavations of the American School of Classical Studies at the Athenian Agora and numerous rescue excavations by the Greek Archaeological Service have brought to light an abundant number of fragments of the history of the city. This archaeological evidence is still awaiting close study and historical interpretation, which will supplement the meager amount of information provided by medieval and early modern literary sources.

In particular, excavations at the Athenian Agora (1933 – present) have revealed an extensive section of the centre of the medieval and post-medieval settlement. This lies on top of the political, religious and commercial centre of the ancient period, just north of the Acropolis hill. Excavations of the medieval and post-medieval periods revealed mainly remains of habitation, but also of industrial and commercial activity.

The area of the Athenian Agora attained a residential character towards the end of the Late Roman period (4th-6th c.), and remained occupied until modern times. Habitation is attested in successive excavation layers, which represent successive chronological phases. The Late Roman period is characterized by the erection of spacious villas, decorated with mosaics and sculpture. During the Early Byzantine period (7th-9th c.) a few of these buildings continued to be used, while other, smaller structures were erected. The Middle Byzantine period (10th-12th c.) saw the expansion of habitation, while industrial activity (such as dyeing or glass production) has been identified in numerous sections of the excavated area. During the 13th c., when Athens was under Frankish occupation, these quarters survived and continued their previous use. The 14th c., a period of high insecurity under Catalan rule, is characterised by contraction of habitation and activity in the Agora: only a few of the earlier buildings are still used or re-erected. When the Ottoman army arrived at Athens, in the mid-15th c., the former city appears to have been transformed into a small town or even village. Activity became more intensive anew during the 16th and 17th c., and continued uninterrupted until the early 20th c., when the excavations of the American School were initiated.

Many questions remain to be answered: How was the town organized during these periods? Is it comparable with other medieval and post-medieval cities of the Eastern Mediterranean? How was the everyday life of the inhabitants? Study of the ceramic finds can provide some answers to the above-mentioned questions, but also to issues regarding food and dining habits, as well as cultural contacts: How high or low was the subsistence level during these chronological periods? Which ceramics or food habits may be considered as ‘local’? How strongly were subsistence levels and dining habits influenced by foreign occupation? What are the trade links of Athens, as suggested by imported ceramic vessels?

In this research context, Athens has been included as a focus point of the VIDI project, run by Dr J. A. C. Vroom (University of Leiden). Within the VIDI project, research focuses both on issues of typology and chronology, as well as on living conditions, food, and cultural contacts, as these emerge from the archaeological evidence of the Athenian Agora.

J.A.C. Vroom & E. Tzavella

Links

http://archaeology.leiden.edu/research/neareast-egypt/byzantine-ottoman

http://archaeology.leiden.edu/research/neareast-egypt/byzantine-ottoman/...

http://www.ascsa.edu.gr/index.php/excavationagora/

http://agathe.gr/research?q=P2120

http://www.eie.gr/archaeologia/En/Index.aspx

http://www.eie.gr/byzantineattica/view.asp?lg=en

Bibliography

Camp J. McK. II – Mauzy C. A. (eds.) 2009. The Athenian Agora: New perspectives on an ancient site, Athens – Mainz am Rhein: ASCSA and Philip von Zabern.

Frantz A. 1938. ‘Middle Byzantine pottery in Athens’, Hesperia 7, 429-467.

Frantz A. 1942. ‘Turkish pottery from the Agora’, Hesperia 11, 1-28.

Frantz A. 1988. The Athenian Agora vol. XXIV. Late Antiquity, AD 267-700, Princeton: ASCSA.

Hayes J. W. 2008. The Athenian Agora vol. XXXII. Roman pottery: Fine ware imports, Princeton: ASCSA.

Hayes J. W. 2008. ‘Tablewares, functional ceramics and ritual pots: creating a typology of Roman-period Athenian products’, in: S. Vlizos (ed.), Athens during the Roman period: Recent discoveries, new evidence, Athens: Benaki Museum, 4th Supplement, 439-447.

Tzavella E. 2008. ‘Burial and urbanism at Athens (4th-9th c. AD)’, Journal of Roman Archaeology 21, 352-368.

Tzavella E. 2010. ‘Pottery from Athenian graves dating to the end of Antiquity’ (in modern Greek), in: D. Papanikola-Bakirtzi – N. Kousoulakou (eds.), Κεραμική της Ύστερης Αρχαιότητας από τον ελλαδικό χώρο (3ος-7ος αι.), Thessaloniki, 649-670.

Vroom, J.A.C. forthcoming. ‘Digging for the ‘Byz’. Adventures into Byzantine and Ottoman archaeology in the eastern Mediterranean’, Pharos XIX.2 (2013).

TARSUS

Historical background

Tarsus is situated in the southern part of central Turkey, 20 km. inland from the Mediterranean Sea. Tarsus was on the eastern border of the Byzantine Empire. It flourished as a trade and military centre because of its strategic location below the Cilician Gates, the main pass through the Taurus mountains of southern Turkey, connecting central Turkey, Syria and the Mediterranean coast. Captured by the Umayyads in 637 C.E., the city passed under Abbasid control in the 8th century and became one of the main centers of the Western thugur, the fortified region on the Islamic-Byzantine frontier. Tarsus attracted ghazis, volunteer soldiers of the Islamic faith from all over the Caliphate, stretching from North Africa to Iran, with provisions and accommodation provided by the support of the wealthy Muslim ruling class. The city was active in commercial activities, land and maritime trade and in the manufacturing of textiles, glass and ceramics. Since then, Tarsus frequently changed hands from the end of the 10th century onward among Byzantines, Armenians, Crusaders, Mamluks, Ramazanids and finally Ottomans and was used for naval operations by Byzantine, Islamic and Crusaders armies.

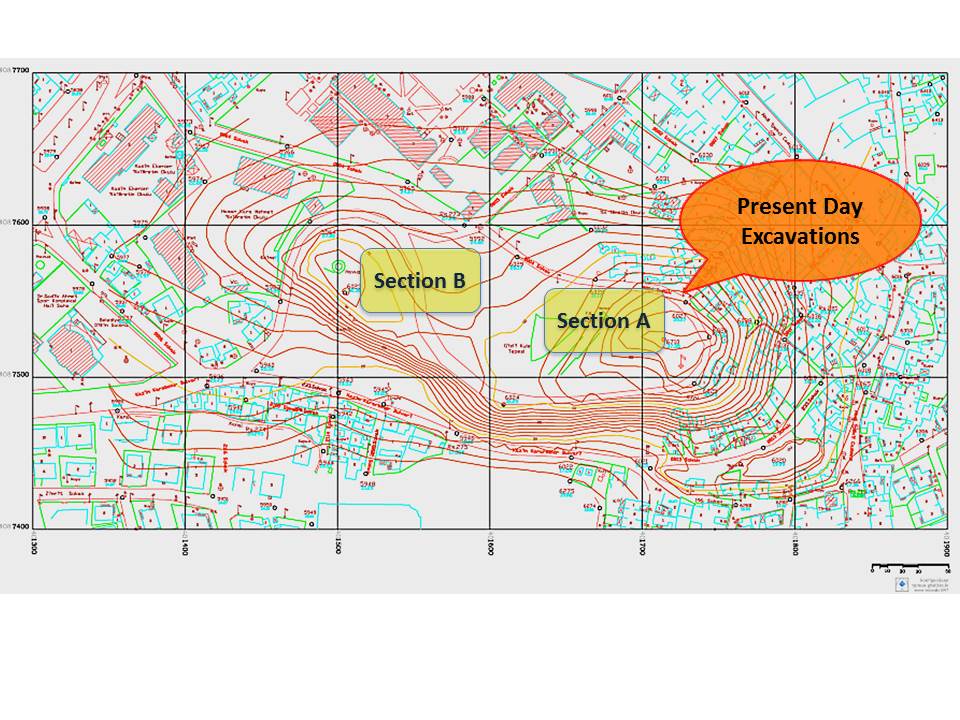

Excavations at Gözlükule

The first excavations on the mound of Gözlükule, situated in the south-western part of the city, was undertaken by an American team led by Hetty Goldman of Bryn Mawr College (U.S.). Supported by the Archaeological Institute of America, the Harvard Fogg Museum and the Institute of Advanced Study, the archaeological project was carried out from 1935 until 1939 and between 1947 and 1948. After a gap of almost 50 years, new excavations began in September 2001 with the collaboration of Bryn Mawr College (Pennsylvania, US) and Bosphorus University (Istanbul, TR) under the direction of Dr. Aslı Özyar. The excavations reveal that the mound was occupied from Neolithic to Late Ottoman times (c. 4500 B.C.E.-1900 C.E.). The Gözlükule Archaeological Project corresponds to one of the rare excavations in Turkey which has an extensive Early Islamic settlement and a considerable amount of Early Islamic to Islamic material finds.

The medieval and post-medieval ceramic material was previously examined by the American pottery specialist Florence E. Day, from the American University of Beyrouth, in the 1930s. However, this study was never published in detail. Recent research reveals that the largest quantity of the material dates to the Early Islamic period (mid. 7th-10th centuries C.E.).

The Ceramic Finds

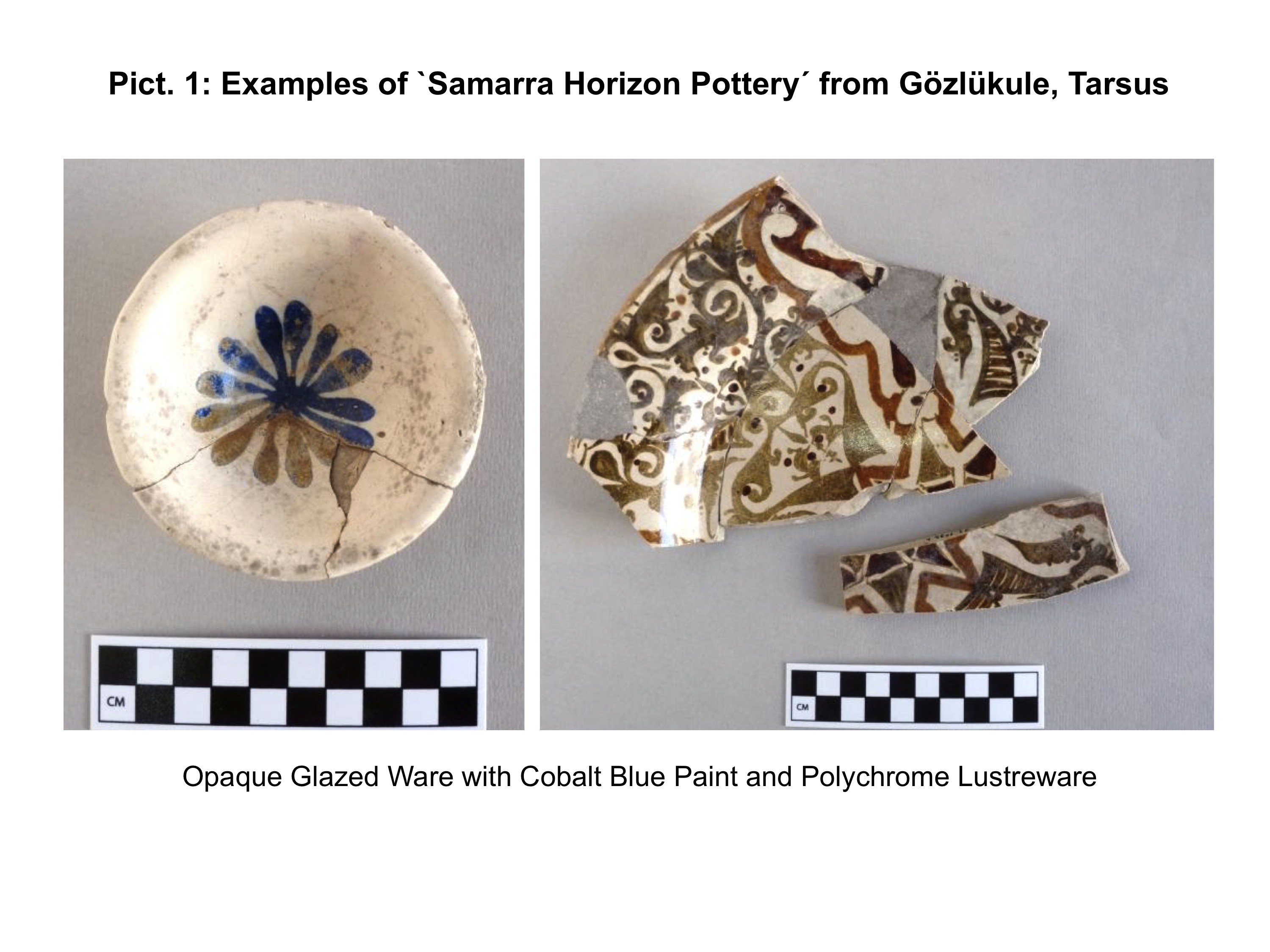

The medieval ceramic assemblage from the old excavations is mainly composed of finewares. Tablewares include the broad range of polychrome glazed wares known as the “Samarra Horizon Pottery”, including Lustrewares, Opaque Glazed Ware with Cobalt Blue Paint, Glazed Relief Ware, Polychrome Splashed and Incised Wares, probably imported from the Abbasid heartland (Pict. 1). In addition to the imported pottery, representing 20% the tablewares, the greatest group of the tablewares corresponds to a probably regionally produced Polychrome Painted Glazed Ware (Pict. 2).

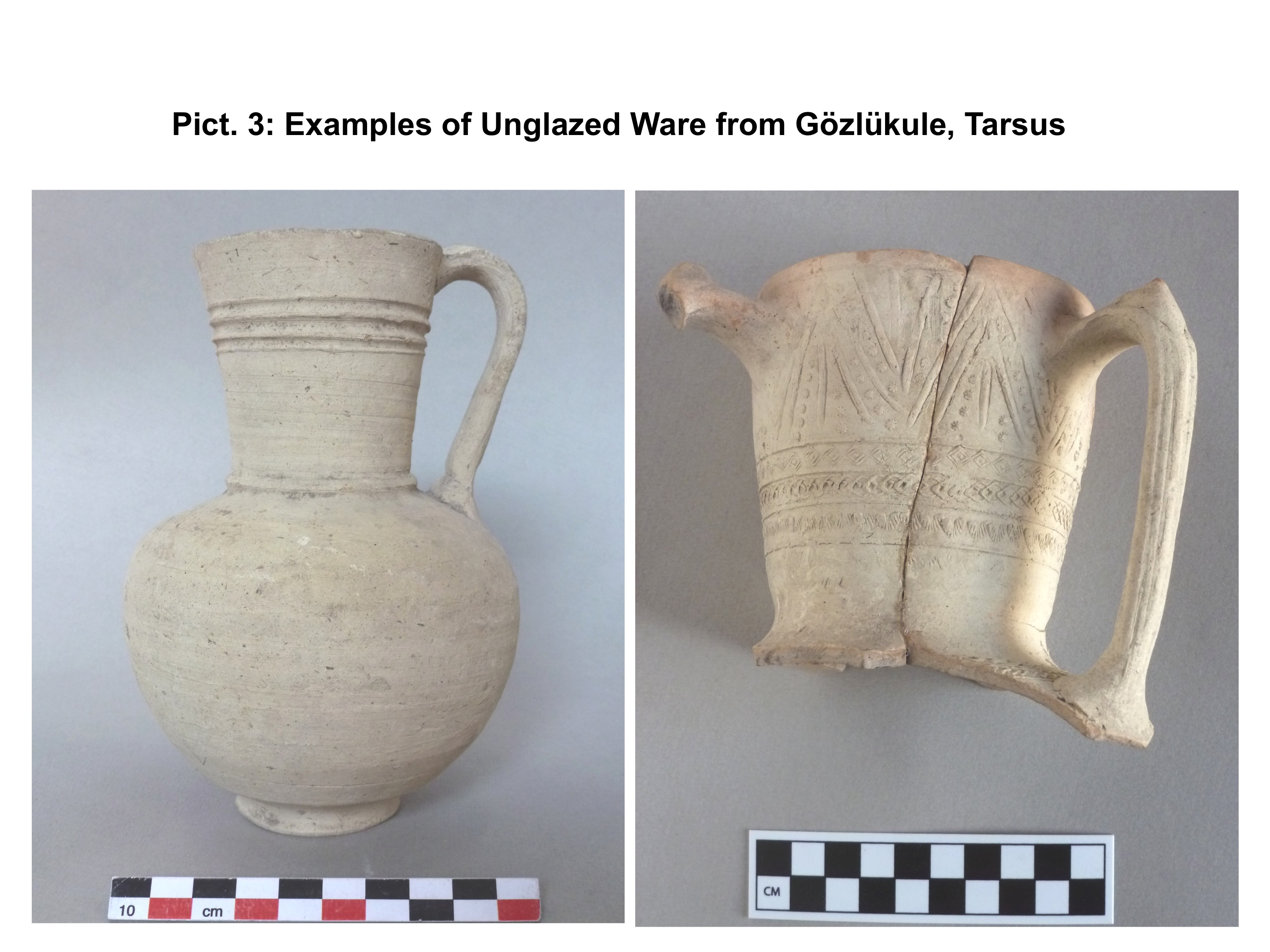

With 76% of unglazed pottery, light utility wares form a large group of the assemblage as well. These light utility ceramics used in the service of liquids are referred as “Unglazed Ware” (Pict. 3). Unglazed Ware appears mainly in closed forms, and is commonly found in Early Islamic sites in the Near East. Among the cooking pots, there are two types. The first one is Brittle Ware, belonging to the Roman tradition, manufactured from an- iron rich, red clay, frequently shaped as medium-sized containers with concave walls. The second type corresponds to Soft Stone Vessel Imitations, which are made of a grey/black fabric. This group includes medium-sized pots with straight walls and lug handles, burnished on the exterior surface and decorated with incised geometric forms.

This specific material culture belonging to a widespread Muslim koinè raises political, socio-economic and cultural questions about the role of Tarsus in the military organization of the Abbasid Caliphate, about its role in the medieval international trade system, and finally about Muslim culinary habits.

J.A.C. Vroom & Y. Baǧcı

Fig. 1: Tarsus, Gözlüküle Mound: map of the old and new excavations.

Fig. 2: Tarsus, Gözlüküle Mound: trench from the new excavations.

Pict.1: Opaque Glazed Ware and Polychrome Lustreware.

Pict.2: Polychrome Painted Glazed Ware.

Pict.3: Unglazed Ware.

Links

Links

http://archaeology.leiden.edu/research/neareast-egypt/byzantine-ottoman/...

http://www.tarsus.boun.edu.tr/

Bibliography

Day, E. Florence. 1941. “Islamic Finds from Tarsus” Asia 41, 143-146.

Goldman, Hetty. 1950, 1956, 1963. Excavations at Gözlükule, Tarsus. Volume1-3. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Özyar, Aslı. 2005. Field Seasons 2001-2003 of the Tarsus Gözlükule Interdisciplianry Research project. Istanbul: Ege Yayınları.

Vokaer, Agnѐs. 2011. La Brittle Ware en Syrie. Bruxelles: Académie Royale de Belgique.

Vroom, Joanita. 2009. `Medieval Ceramics and the Archaeology of Consumption in Eastern Anatolia`. In: T. Vorderstrasse and J. Roodenberg (eds.), Archaeology of the Countryside in Anatolia. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, 235-258.